A decade ago, Suzanne Topalian, M.D., led a team of researchers who made an astonishing contribution to how cancer is fought. Many cancers can “put the brakes” on the body’s immune cells — cells that would normally storm into a tumor and destroy it. Topalian, director of the Melanoma Program at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and associate director of the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, and others developed a class of drugs called immune checkpoint blockers, which take the brakes off the immune system and give it a chance to fight back against cancer.

“Now, every oncologist is engaged in immunotherapy. These drugs are becoming a common denominator for cancer therapy,” Topalian says.

But as the drugs are approved for more types of cancer and used by more patients, oncologists still have questions they want to answer about cancer immunotherapy, says Topalian.

Which patients will respond best? Scientists are in the midst of a huge hunt for biomarkers — which can be anything from genetic mutations to proteins sampled from tissue or blood — that can help them determine which patients are most likely to benefit from immunotherapies, such as checkpoint blockers. There are some cancer treatments that target single genetic mutations, “but immunotherapy biomarkers are a bit more complex than that” and could involve a number of genes and proteins, Topalian says.

Johns Hopkins researchers have played leading roles in searching for these biomarkers, she says. For instance, in 2015, a team of Johns Hopkins oncologists found genetic biomarkers that identified a small group of colon cancer patients who responded well to a checkpoint blocker. “We need more sensitive and more specific markers like this to help us learn which patients are most likely to do well with these treatments,” says Topalian.

Can we combine immunotherapy with other treatments? “We know from lab studies that some of these checkpoint blocker therapies are potent, but they’re even more powerful when you combine them with other drugs,” Topalian notes.

Numerous clinical trials at Johns Hopkins and elsewhere are testing these combinations, whether adding a standard therapy, like radiation or chemotherapy, to a checkpoint blocker or combining an immunotherapy drug that lifts the brakes from the immune system with another drug that revs up the immune system. In some trials, Topalian says, both of the drugs could be still be experimental, “which is a new frontier for drug development.” The hope, she says, is that drug combinations that contain some kind of immunotherapy could extend the success of these drugs in difficult-to-treat cancers, like metastatic pancreatic, prostate, and head and neck cancers.

Can we improve how we deliver cancer immunotherapies? For the moment, checkpoint blockers are given to patients intravenously every two to three weeks during an hourlong treatment. But Topalian says scientists are studying whether this is really the best way to give these drugs, or if there might be a way to deliver them as a pill or in a form that requires less frequent clinic visits.

As more patients begin to benefit from these drugs, she notes, “We’re also doing active research to find out how long we can or should keep administering these drugs to patients, whether it’s months or years or indefinitely.”

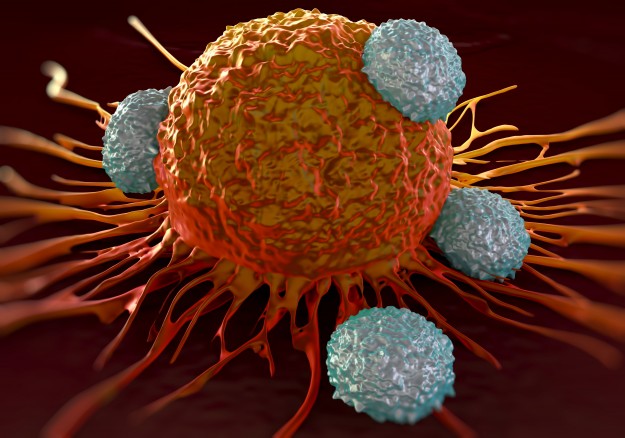

What more can we tell patients about these treatments? “I think people are fairly well-informed about this, but it’s important to remember that this is a different kind of therapy because it doesn’t directly kill tumor cells,” Topalian explains. “This therapy treats the immune system, and then the immune system attacks cancer cells.”

Patients may worry about side effects from immunotherapy, especially whether the treatment will cause their immune systems to attack normal, healthy tissue. “Most of the side effects that we see are mild and managed fairly easily,” such as fatigue or rashes, says Topalian.

Topalian also wants patients to know that the work on immunotherapies — even ones that are already being used to treat cancer — never stops. “We study these drugs in patients and then in the lab and then back again to better understand how they are working,” she says. “For patients with cancer, I think there’s more reason than ever to be hopeful.”

Dr Topalian,

Thanks for all you do and are doing to perfect this newer way to treat cancer. I follow all you work and hoping and praying for a Melanoma cure for my daughter Melissa Walling and others like her. This was a interesting read and sounds promising.

Sincerely,

Marie Walters

Interesting read.

Please include MDS in your treatment discussions especially in your Kimmal reports

Many thanks for your comment. More information is also available here: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/types_cancer/myelodysplastic_syndrome.html

Comments are closed.