We invite you to use the comments section to share your memories and tributes to Dr. Coffey.

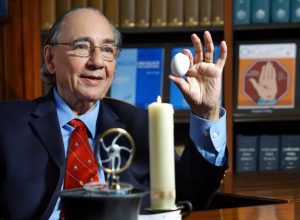

Donald Coffey, a distinguished Johns Hopkins professor and prostate cancer expert, who was the former director of the Brady Urological Research Laboratory and deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, died on Nov. 9 at the age of 85.

Donald Coffey, a distinguished Johns Hopkins professor and prostate cancer expert, who was the former director of the Brady Urological Research Laboratory and deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, died on Nov. 9 at the age of 85.

In his more than 50 years at Johns Hopkins, Coffey amassed a long list of accomplishments. Many of the accolades are as unconventional as the man. He chaired the Department of Pharmacology without ever taking a course in pharmacology. With no medical degree, he helped found the Cancer Center in 1973 with its first director, Albert Owens, and then ran it briefly in 1987.

Coffey, who became one of Johns Hopkins’ first triple professors, began his career washing glassware for graduate students. He worked at Westinghouse designing radar antennas during the day, and in the evening, he took classes and worked in the urology laboratory. In 1959, he was named the director of the Brady Urological Research Laboratory. After a year of running the lab, he was accepted into the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s graduate program in biochemistry.

“Don touched so many of us in such profound ways that it is hard to imagine life without him. We know how fortunate we have been to know him and experience his special and wonderful uniqueness. So, we are only really without him in body, but not in soul,” says Kenneth Pienta, M.D., director of research for the Brady Urological Institute at Johns Hopkins and the Donald S. Coffey Professor of Urology.

In 1964, Coffey earned his Ph.D. at 33 years of age, and by then, he had already been a chemist, an engineer, a laboratory director and prostate cancer researcher. He became the Catherine Iola and J. Smith Michael Distinguished Professor of Urology—as well as professor of oncology, pharmacology and molecular sciences, and pathology—and a member of the professional staff of the Applied Physics Laboratory. He is also a former president of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). His many awards include the Fuller Award and Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Urological Association, an American Cancer Society Distinguished Service Award, and the AACR Margaret Foti Award for Leadership and Extraordinary Achievements in Cancer Research.

“The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) is deeply saddened by the loss of Dr. Donald Coffey, a Past President of the AACR and Fellow of the AACR Academy” said Margaret Foti, Ph.D., M.D. (hc), chief executive officer of the AACR. “His outstanding leadership skills, dedication to mentoring young investigators, passionate advocacy for sustained increases in funding for cancer research, and remarkable ability to translate complex scientific concepts into lay language made him an icon in the field and a true champion of cancer research. In his memory and honor, we will do our utmost to work even harder to expedite the prevention and cure of all cancers.”

Coffey’s early research was in many ways the bedrock on which modern genetic and epigenetic discoveries at Johns Hopkins were built. In 1974, he challenged the popular thought on how DNA was copied, looking instead to the core of the nucleus. At the time, it was a revolutionary idea. Most scientists believed there was nothing inside the core. Coffey brought together two young scientists who were new to the field of cancer research and are now leaders in cancer immunology and cancer genetics: Drew Pardoll, M.D., Ph.D., and Bert Vogelstein, M.D.

Coffey revealed that the nucleus has a skeleton, which he dubbed the nuclear matrix.

He described cancer as the body’s genetic tape playing the wrong song at the wrong time and set out to discover what decides which tape is played and when, and how that contributes to the uncontrolled cell growth that is the hallmark of cancer.

“He may be the most remarkable person I’ve ever met. His impact on cancer and the people who will ultimately solve the cancer problem is immeasurable,” says William Nelson, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and a former trainee of Coffey’s.

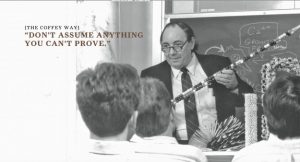

Coffey was a beloved teacher and mentor and was well-known for using Slinkies, soap bubbles, soda cans and more to illustrate a point. For his nuclear matrix work, he bought a jigsaw and built an award-winning scale model, 175 feet long, of a relaxed single loop of DNA magnified 25 thousand times. For Coffey, neither the classroom nor the laboratory ever closed. In the hallways of Johns Hopkins, in his office over high tea or in a conference room, he could be found fostering collaborations and inspiring innovative ideas about cancer.

“As the patriarch of prostate cancer research, his teaching influenced entire generations of cancer researchers worldwide. He was the original pioneer of bench to bedside research, now known as translational medicine. He was innovative, always thinking and full of creativity,” says William Isaacs, Ph.D., professor of urology, who came to Johns Hopkins in 1977 as a laboratory technician for Coffey. “He changed people’s lives in a single hour. It’s impossible to exaggerate the impact he had. He loved science, but he really loved helping people. He had a gift for connecting with people.”

Coffey suffered from dyslexia, a disorder that caused him to struggle as a student but helped make him one of Johns Hopkins’ greatest teachers. He was recently awarded the Dean’s Distinguished Mentoring Award.

Coffey suffered from dyslexia, a disorder that caused him to struggle as a student but helped make him one of Johns Hopkins’ greatest teachers. He was recently awarded the Dean’s Distinguished Mentoring Award.

"Don Coffey's outrageously original lecture during my first year of medical school ignited my interest in becoming a physician-scientist. Thirty-six years later, that spark came full circle when I had the honor to speak at the celebration of his Distinguished Mentoring Award. He will be dearly missed, but his impact will live o for generations to come,” says Charles Sawyers, M.D., Chair, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Coffey is well-remembered by the Johns Hopkins community for his annual St. Patrick’s Day lecture on the Origins of the Creativity of Man.

Born in Bristol, Tennessee, on Oct. 10, 1932, Coffey is survived by his wife of 64 years, Eula; his daughters, Kathryn Craighead and husband Michael, Carol Burns and husband Patrick; grandchildren Sarah Craighead Liske, Emilyann Craighead, Brian and Alana Burns; and great-grandchild Caiden Liske. He was the brother of Kerry Hale and husband Lewis and was predeceased by sister Ellen Wagner and brother Wallace Coffey.

More on the Web:

Watch a video: The Donald Coffey Story

Prostate Cancer Discovery: Teacher’s Teacher, Scientists’ Scientist

“The Coffey Way”, Promise & Progress, page 24

Coffey anecdotes:

I met Don Coffey in 1961 while I was an Osler resident. He had signed himself into the Hospital as a patient, so the house staff could supervise his taking a diet which for 6 weeks was restricted to coffee and water alone! Unfortunately, this noble experiment ultimately failed!

Years later, in discussing scientific topics of mutual interest, I offered to send Coffee some reprints. But, instead of reading them, he insisted on making a special trip to my office in Stony Brook, New York, to discuss their contents with me in person, after which he returned immediately to Baltimore. According to Don, his dyslexia was so severe that he preferred to receive detailed information orally. Despite this handicap, his intellect was that of a true polymath.

When Don gave a research seminar at Stony Brook, he insisted on using two projectors at the same time, a difficult but remarkable effective way of capturing the audience’s attention while conveying the subject at hand.

Don Coffee truly was one of a kind!

I will personally miss Don Coffey in so many ways. I never failed to learn something each and every time I was in his presence. Don was always some one I could turn to as a faculty member at Hopkins and later on while at NCI, there was never a time that he was too busy or not available when I needed his advice or his help. Most of all, there will be a very big void in the best dinner conversations ever. j

Comments are closed.