Breast cancer researcher Sara Sukumar, Ph. D., and her colleagues have developed a unique platform that can quickly and accurately distinguish benign breast tumors from breast cancers.

A patient’s needle aspiration sample of the lesion is loaded into cartridges and inserted in a machine that returns results within five hours. (Needle aspirations involve using a thin needle and a syringe to pull out cells, tissue and fluids from the lesion). Noting that the number of breast cancer cases is rising around the world, she believes this platform could shrink the time from diagnosis to treatment, which is particularly important for low- and middle-income countries, which may experience delays of up to 10 months for a treatment plan to take effect.

The test could be used in screening clinics to detect malignancies and assist in prioritizing patients who need accelerated pathological and clinical evaluation, while reducing the burden on overtaxed health systems. For example, a retrospective analysis from Malawi, a country in southeastern Africa, identified a median turnaround time of 43 days for pathological diagnosis of cancer specimens paid out-of-pocket, and 101 days for nonpaid specimens which rely on state funds.

Sukumar’s test detects methylation, a type of chemical tag, in one or more of nine genes that are altered in breast cancers, but not in harmless benign tumors.

In collaboration with the Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, its National Health Laboratory Services, the WITS Foundation in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the diagnostic company Cepheid, Sukumar is leading a clinical study of 700 women. The study, which is ongoing, will collect fine needle biopsies obtained from women with tumors of various sizes to confirm that the cartridge-based platform can accurately distinguish benign tumors from malignant cancers.

Sukumar, the Barbara B. Rubenstein Professor of Oncology, says “Diagnosis is a huge bottleneck to starting treatment, especially in countries that have a small number of pathologists available to review breast cancer biopsies and who serve a huge population. A test like ours could be especially useful in places with meager resources and where mortality rates from breast cancer are much higher compared to the developed world.”

She believes that, in the future, the test will allow women to be diagnosed where they live and earlier, due to the widespread availability of the machines, which are also commonly used to detect infectious diseases in countries like Africa and India.

“They don’t have to wait until the tumor grows to a size that can be self-detected by breast palpation,” she says. “In the absence of breast cancer screening, perhaps educating the women will make them self-aware and prepared to accept annual screening at least by AI-guided ultrasound.”

She is collaborating with radiologists to put this much-needed resource into place in Africa. She envisions that in a screening clinic, an ultrasound may detect a suspicious growth in the breast of a woman, and the cartridge assay will determine if it is a cancer or benign. Women with suspected cancer will be transported to the hospital for more detailed testing to confirm a diagnosis, leading to expedited treatment.

“Triaging patients, using the test, to focus timely attention on those who need it is a big contribution to the health system in these countries. It will save lives,” says Sukumar.

Since the test measures molecular markers, it has the potential to detect breast cancer at its earliest stage.

“Instead of coming into the clinic with Stage 3 or 4 breast cancers, our hope is to take measures, step by step, to detect them at Stage 1 or even Stage 0,” says Sukumar.

If the study finds the test works as anticipated, she envisions the potential for an annual test to alert doctors to the presence of an early cancer and to get women with malignant tumors to treatment sooner.

“Our colleagues in South Africa have been wonderful. They have put everything into place, and work is progressing at a remarkably fast pace. We think a successful test will have a great impact on early detection, and many, many lives could be saved,” says Sukumar.

Sukumar and the team expect to have the results of the study by mid-2025, two years ahead of schedule. Already, however, they see some trends emerging. She says they expected an approximately even distribution of benign and malignant tumors, but so far, she says, nearly 70% have been malignant. Also, many of the women with breast lesions are in their 30s.

“Most of the lesions in the younger women are benign, but it raises the question of why they are getting lesions at such a young age and whether screening should begin at an earlier stage,” says Sukumar.

Guiding Treatment

Sukumar is also studying whether the test could be used to guide treatment, using the same molecular markers that pointed to the cancer to show whether a patient’s breast cancer is responding to therapy. DNA shed from the patient’s tumor into the bloodstream could be placed in the cartridge, and the level of methylation measured.

Patients with unchanged or rising methylation patterns during neoadjuvant (chemotherapy before surgery) therapy, which indicates tumor cells still remain in the body, may need continued treatment with the same drug combination or even a new drug combination. On the other hand, women who do not show any signs of methylation may be able to proceed directly to surgery.

They have already shown in U.S. studies that the cartridge platform was able to identify the presence of cancer DNA in one or more of nine genes in blood samples from women actively undergoing treatment for metastatic breast cancer. The study also showed that high levels of methylation correlated with significantly shorter progression-free survival (the length of time in which the disease does not worsen) and worse overall survival than those who had low levels of methylation in the same genes.

Sukumar says they are still optimizing the test to detect cancer DNA shed into the bloodstream at earlier stages of cancer. The next steps include studying patterns of methylation seen each week after starting treatment to identify the optimum time to measure cumulative methylation, and to validate and refine the model in similar patient populations and in patients with early-stage disease.

Her current studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health through an industrial-academic partnership and a Department of Defense grant. With additional funding, Sukumar says, she could begin to apply the test to earlier stages of breast cancer and expand it to other cancer types. She is exploring its potential in cervical and prostate cancers and is collaborating with researchers in Nigeria to see if the test could be applied to detecting colon cancer.

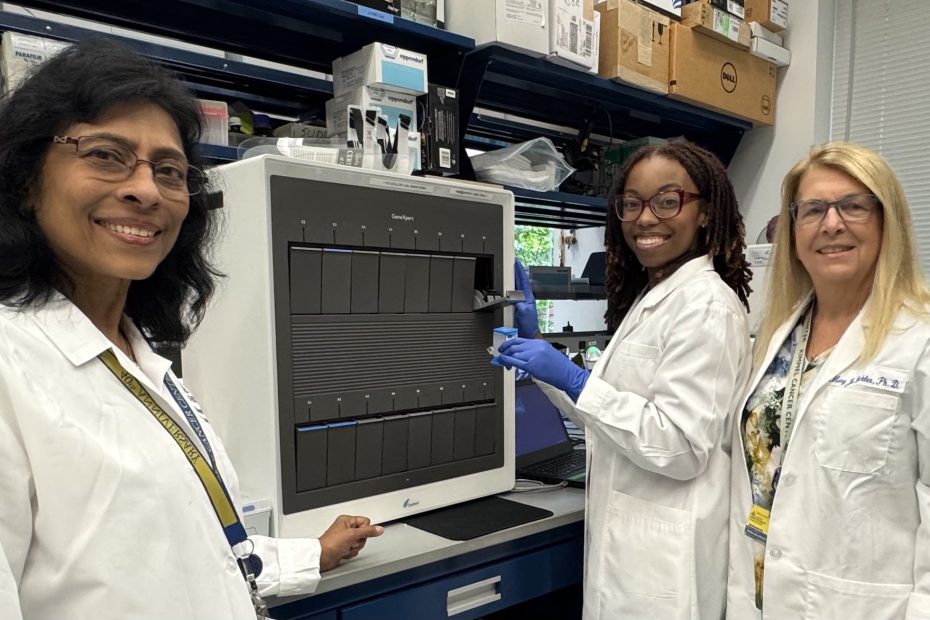

Her team of Johns Hopkins collaborators are Mary Jo Fackler, Ph.D., Leslie Cope, Ph.D., Christopher Umbricht, M.D., Ph.D,. Antonio Wolff, M.D., and Kala Visvanathan, MD. M.P.H., with assistance from Madison Pleas, B.S.